Introduction

Shenandoah National Park is an American national park that encompasses part of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Almost 40% of the land area—79,579 acres (124.3 sq mi; 322.0 km2)—has been designated as wilderness and is protected as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. The highest peak is Hawksbill Mountain at 4,051 feet (1,235 m).

As stated in the foundation document:

"Shenandoah National Park preserves and protects nationally significant natural and cultural resources, scenic beauty, and congressionally designated wilderness within Virginia’s northern Blue Ridge Mountains, and provides a broad range of opportunities for public enjoyment, recreation, inspiration, and stewardship."

History of the Park

Initial Legislation

Legislation to create a national park in the Appalachian mountains was first introduced by freshman Virginia congressman Henry D. Flood in 1901, but despite the support of President Theodore Roosevelt, failed to pass. Acadia finally broke the western mold, becoming the first eastern national park. It was also based on donations from wealthy private landowners. Stephen Mather, the first NPS director, saw a need for a national park in the southern states, and solicited proposals in his 1923 year-end report. In May 1925, Congress and President Calvin Coolidge authorized the NPS to acquire a minimum of 250,000 acres (390.6 sq mi; 1,011.7 km2) and a maximum of 521,000 acres (814.1 sq mi; 2,108.4 km2) to form Shenandoah National Park, and also authorized creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. However, the legislation also required that no federal funds would be used to acquire the land. Thus, Virginia needed to raise private funds, and could also authorize state funds and use its eminent domain (condemnation) power to acquire the land to create Shenandoah National Park.

Aquisition of Park Lands through Eminent Domain

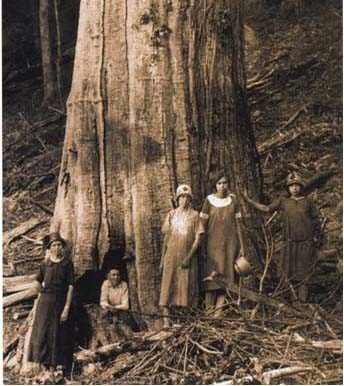

The commonwealth of Virginia slowly acquired the land through eminent domain, and then gave it to the U.S. federal government to establish the national park. Some families accepted the payments because they needed the money and wanted to escape the subsistence lifestyle. Nearly 90 percent of the inhabitants worked the land for a living: selling timber, charcoal, or crops. They had previously been able to earn money to buy supplies by harvesting the now-rare chestnuts, by working during the apple and peach harvest season (but the drought of 1930 devastated those crops and killed many fruit trees), by selling handmade textiles and crafts (displaced by factories) and moonshine (illegal after Prohibition started).

When many families continued to refuse to sell their land in 1932 and 1933, proponents changed tactics. Freeman hired social worker Miriam Sizer to teach at a summer school he had set up near one of his workers' communities and asked her to write a report about the conditions in which they lived. Although later discredited, the report depicted the local population as very poor and inbred and was soon used to support forcible evictions and burning of former cabins so residents would not sneak back. University of Chicago sociologists Fay-Cooper Cole and Mandel Sherman described how the small valley communities or hollows had existed "without contact with law or government" for centuries, which some analogized to a popular comic strip Li'l Abner and his fictional community, Dogpatch. In 1933, Sherman and journalist Thomas Henry published Hollow Folk[16] drawing pitying eyes to local conditions and "hillbillies."[17][18][19] As in many rural areas of the time, most remote homesteads in the Shenandoah lacked electricity and often running water, as well as access to schools and health facilities during many months. However, Hoover had hired experienced rural teacher Christine Vest to teach near his summer home (and who believed the other reports exaggerated, as did Episcopal missionary teachers in other Blue Ridge areas).

Building the Park: Creating Jobs through the CCC

The creation of the park had immediate benefits to some Virginians. During the Great Depression, many young men received training and jobs through theCivilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The first CCC camp in Virginia was established in the George Washington National Forest near Luray, and Governor Pollard quickly filled his initial quota of 5,000 workers. About 1,000 men and boys worked on Skyline Drive, and about 100,000 worked in Virginia during the agency's existence.[22][23] In Shenandoah Park, CCC crews removed many of the dead chestnut trees whose skeletons marred views in the new park, as well as constructed trails and facilities. Tourism revenues also skyrocketed. On the other hand, CCC crews were assigned to burn and destroy some cabins in the park, to prevent residents from coming back.

Final Creation of Shenandoah and the "Ickes List"

Shenandoah National Park was finally established on December 26, 1935, and soon construction began on the Blue Ridge Parkway that Byrd wanted.[24] President Franklin Delano Roosevelt formally opened Shenandoah National Park on July 3, 1936. Eventually, about 40 people (on the "Ickes list") were allowed to live out their lives on land that became the park. One of them was George Freeman Pollock, whose residence Killahevlin was later listed on the National Register, and whose Skyland Resort reopened under a concessionaire in 1937. Carson also donated significant land; a mountain in the park is now named in his honor and signs acknowledge his contributions. The last grandmother resident was Annie Lee Bradley Shenk. NPS employees had watched and cared for her since 1950; she died in 1979 at age 92. Most others left quietly. 85-year-old Hezekiah Lam explained, "I ain't so crazy about leavin' these hills but I never believed in bein' ag'in (against) the Government. I signed everythin' they asked me."

Attractions

The park is best known for Skyline Drive, a 105-mile (169 km) road that runs the length of the park along the ridge of the mountains. 101 miles (163 km) of the Appalachian Trail are also in the park. In total, there are over 500 miles (800 km) of trails within the park. There is also horseback riding, camping, bicycling, and a number of waterfalls. The Skyline Drive is the first National Park Service road east of the Mississippi River listed as a National Historic Landmark on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also designated as a National Scenic Byway.

Campgrounds, Cabins, and Lodges

Most of thecampgroundsare open from April to October–November. There are five major campgrounds:

- Mathews Arm Campground

- Big Meadows Campground

- Lewis Mountain Campground

- Loft Mountain Campground

- Dundo Group Campground

There are three lodges/cabins:

- Skyland Resort

- Big Meadows

- Lewis Mountain Cabins

Rapidan Camp, the restored presidential fishing retreat Herbert Hoover built on the Rapidan River in 1929, is accessed by a 4.1-mile (6.6 km) round-trip hike on Mill Prong Trail, which begins on the Skyline Drive at Milam Gap (Mile 52.8). The NPS also offers guided van trips that leave from the Byrd Center at Big Meadows.